Thirty Years of Ringside Stories: Gareth A Davies Reflects on His Career

Gareth A Davies

In an interview for Global Networker, Gareth A Davies reflects on his three-decade career in sports journalism, highlighting his deep connection with combat sports and the personal journey that shaped his storytelling.

Gareth, your career spans over three decades, during which you’ve delved deep into the worlds of sports, especially boxing and MMA. However, let’s go back to the beginning of your story. How did your professional path begin?

It goes back to childhood. As a hyperactive, outdoor child, I played so much sport growing up — rugby, cricket, and always had a love of and fascination for martial arts. I was always very competitive. I was fascinated by how energy and life force are applied, and how the ancient survival instincts in human beings come to the surface.

I did not see these things’ philosophical, physical, or even psychological complexities in such a complex way when I was so young, but they were there. I also loved reading about military history and stirring adventures. Later on, many of those things came to the fore in my life. I loved writing and exploring the world, delving into cultures. I still do. Education is a process… and never ends.

I feel fortunate, because I had the privilege of travelling the world with my parents, firstly in the military, and later in the Foreign Office, and was therefore exposed to colour, culture, and creed. As a family, we were in Berlin, Vienna, Hong Kong, Moscow, Warsaw, Lagos, Nicosia, Beijing and other capital cities. It was a busy life, rich with experiences and global networking. It developed a natural study of countries, boundaries, and the DNA of different peoples.

I almost followed the same path as my parents and thought about being a foreign correspondent, which was the case briefly. But after boarding school and University in England (initially a modern languages degree BA Honours, and then a Master’s Degree in Linguistics and Journalism) I went to live in China for a year. That was where my journalism began, covering Tian An Men Square and the student revolt against the Chinese Government in 1989. It was fast-moving, I have to admit thrilling at times, but ultimately, of course, a tragedy. I also studied martial arts there, wushu, tai chi, and chi ghung, and studied Chinese. It was my ‘year of living dangerously’.

My early heroes were Muhammad Ali and Bruce Lee. Ali because of his brilliance, activism, free spirit, and uniqueness as a boxer and entertainer. Bruce Lee because he was so dynamic, so innovative, and always had a rose for the girl, too. Huge influences on my life.

My written journalism began in Beijing in 1989/90, and on returning home in 1990, I worked for local London newspapers, then The Daily and Sunday Telegraph from 1993, and I’m still writing for them today. The Telegraph has become my home from boy to man.

In that time, I have written on sports, features, and long pieces for weekend magazine and foreign reports. Three decades have gone by very quickly, and my foreign correspondence was cut short by having two beautiful daughters in my early twenties.

Early on in my career, I also worked shifts at Agence France-Presse, the Press Association, and other media outlets. That’s where you learn to write quickly, accurately, and simply.

For the last two decades, I have also worked on radio and television, interviewing and presenting. Yet writing is probably the hardest and most rewarding. I have a passion for speaking and broadcasting, telling stories, but there is something special about the written word.

One of the great journalists in history, Samuel Johnson — from many moons ago — left great advice for those of us in the profession: “Research meticulously, simplify, then exaggerate…” he wrote. It always holds. That is the art of storytelling. Johnson also said, “When a man is bored of London, he is bored of life…”. And I tend to agree. London is my home city, and will always be.

This summer, I’m heading to my eighth summer Paralympic Games — they are in Paris — and my body of work on the Paralympic Games since 1996 is something I’m very proud of. The Telegraph has won three world awards for our coverage of the Paralympics, which to me is bigger than sport. It changes the perception of disability on a global scale, and I believe in its motto of ‘mind, body and spirit’. The athletes so often remind me of fighters, with their unique triumph of the human spirit. Every Paralympian has a story…

Gareth A Davies

With such a rich tapestry of experiences in combat sports journalism, could you share a particularly memorable moment or interview that has left a lasting impression on you? What made it stand out?

There are almost too many to mention. Chatting to the great Mike Tyson about darkness and light in our lives. Mike is a remarkable human being, given what he has been through. One of the greatest transformations of any sportsperson living today.

Largely, what I recall are the sensitivities and vulnerability of fighters. I remember a long chat with Prince Naseem Hamed on Islam and Sufi-ism, not boxing.

An emotional interview with the great Ukrainian Oleksandr Usyk, who was talking about being on the front line fighting for his country and visiting injured soldiers in hospital. It was truly moving. There was a zoom with the Klitschko brothers from their hideaway in Kyiv during the start of the invasion by Russia. Heroic, Stoic figures who have transcended sport.

I will add to that the Tyson Fury rise and fall, and in recent times, the amazing investment of the Saudi Arabians and His Excellency Turk Al-Alsheik. It has been fascinating to discuss with the Minister’s team the potential growth in boxing and the changes they want to bring in. His Excellency is a maverick genius.

In the UFC, Dana White is an extraordinary character and the one, who I would call a friend, even though I no longer work directly with the UFC. But it was a rewarding time being on the ground, helping it to grow, helping to change perception through media coverage for just over a decade between 2006 and 2018. It’s now the richest combat sports league in the world, a behemoth in sporting terms. Back then it was about changing perception, which is an omnipresent aspect of my work from the beginning, and even today.

Gareth A Davies and Jake Paul

You’ve been at the forefront of bringing MMA into mainstream coverage. How do you navigate the complexities of these evolving sports, ensuring accurate and engaging storytelling while respecting their traditions and nuances?

It’s always about the narrative and humanizing fighters in what is an ancient art, a calling. It is an honest profession, it is raw and transparent, fighters are gladiators, and promoters are the emperors. That’s how I see it. I think it has always been that way.

How has your perception of boxing and MMA changed over the years of working with these topics?

My perception has not changed really. They are both complex sports, and will always be so… But my empathy for fighters grows deeper. It is the most important commodity we have and should feel, in the telling of peoples’ stories. And it involves trust and openness.

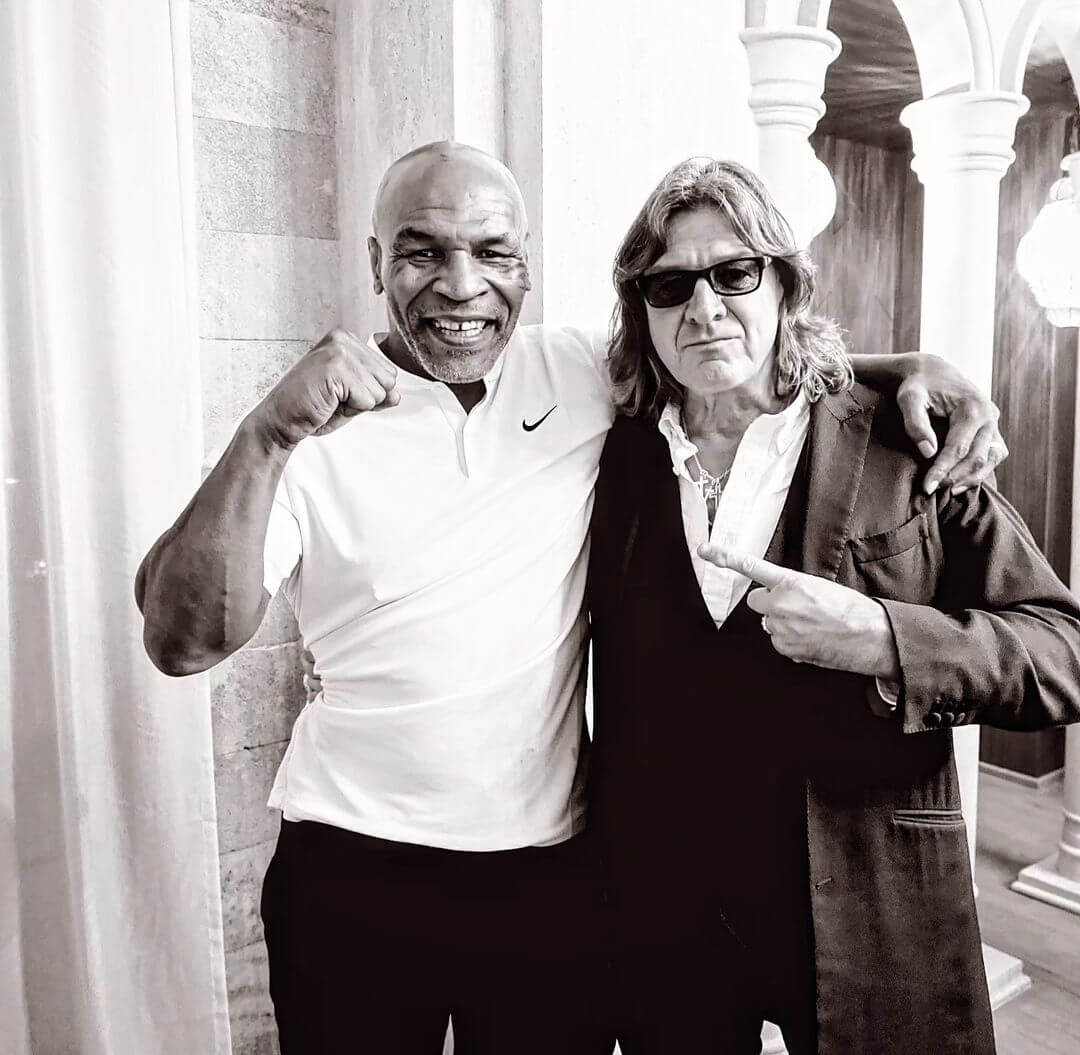

Mike Tyson and Gareth A Davies

Beyond reporting, you’ve also ventured into documentary work, including projects like “Pistorius” and “Manny The Movie.” How does your approach to storytelling differ between the written word and visual media?

Weirdly it’s easier. Manny Pacquiao is a story of triumph, one of the greatest living sports stories, the kid who grew up in a shanty town, became a global sports star and ran for the present. His story is so much bigger than boxing. It was an honour to be invited to be in the documentary film by Leon Gast, who produced the Oscar-winning ‘When We Were Kings’, which told the story of The Rumble in the Jungle, between Ali and George Foreman in 1974 in Kinshasa, Zaire. They were the kings then.

Oscar Pistorius is a very strange one for me because I was close to Oscar for a decade, and yet this tells the story of an anti-hero, the destruction of a dream in one act, about the boy with no legs who ran in the Olympics, and then murdered his girlfriend on Valentine’s Day. I attended court in South Africa during his trial, and it was very peculiar to witness. How a life can change, can ruin others, through a reckless act. The rewards are there in being involved in documentaries, as so many of us now consume them. I hope to be involved in many more.

You’ve interviewed countless fighters and personalities. Is there a common thread or quality you’ve observed among those who excel in combat sports, both inside and outside the ring or cage?

That is a calling. The lessons in the fight world are condensed and intense, and they are emblematic of the life lessons. Everyone and anyone can have a go at the marathon, golf, tennis, but not everyone can fight.

Fighters, for me, fight for a reason deep inside themselves. Proving something, insecurity, vulnerability, anger… things have happened in their lives, and they just need to express themselves.

Gerard Butler and Gareth A Davies

With the rise of social media and digital platforms, the landscape of journalism has undergone significant changes. How do you adapt to these shifts?

I stay true to four things, four rules, no matter what: you are who you mix with, you reap what you sow, and be yourself. Then, I will only write what I would say to someone’s face. Journalism has changed so much. But we are always adapting. We have to. There is no choice; it’s so important. At least 80 percent of my work now appears on social media. It has changed the landscape, in some cases for the better, but also — for the worst. But there are several algorithms now rather than it being linear which is how it was when I started, but the world has changed. But I do believe: if you snooze — you lose. You have to keep up with the times. Having said all that, we all recognize what a story is… the key is how it is presented.

You’ve described yourself as a storyteller by nature. How do you balance the need for compelling narratives with the responsibility to report facts accurately, especially in the fast-paced world of combat sports?

Again, honesty. That rule again — that I will only write or say anywhere what I would equally say to a fighter’s face if he or she is present. Women’s boxing is growing, and that is interesting. In ancient history, when we were tribes, there were most likely two neuro-tribes: the hunters and the gatherers. The hunters (for me the modern pro-fight world characters belong in this group) would have successfully hunted the giant buffalo — men and some women, maybe 90pc to 10pc — to keep the whole tribe alive through the winter months.

I’ve worked in one hundred cities, in 40 countries and the best answer I can give you is that no matter where you are in the world, no matter what time it is. Consistency is a key.

Frank Warren, Gareth A Davies, Eddie Hern. Portrait: Mark Robinson

Can you share a moment of adversity that tested your professional resolve, and how did you overcome it?

Not really, every test is just a lesson. I have always refused to write an angle on a story I do not believe in. I have always held strongly to that, and I have argued many times with my editors over it. But in a wider sense, I do not like resentment, in any way, in life. It is an ugly quality. Sometimes I have had to stand hard against resentment.

I believe strongly that it is also great to pass things on to younger people coming through that you know will bring wisdom. But moments of adversity help you grow. In those moments, you find out about yourself. Perhaps I have been blessed by having a few older mentors in the fight world — the writer Colin Hart, promoters Bob Arum, Frank Warren, and Barry Hearn — and some fine journalists at the start of my career, who I think helped with wisdom in the toughest aspects of the job. I was taught that how you deal with sleeplessness, show your stamina, work through exhaustion — I’ve missed one deadline in my life — show how adept you are at work. And the longer you do the job, clearly, it is the right calling.

Looking ahead, what do you envision for the future of sports, and what role do you hope to play in shaping that future as a respected and resonant voice in combat sports journalism?

Sport will always be here. Professional sport, which, by its very name and nature, is driven and governed by money. We are just witnessing the first undisputed heavyweight title in 25 years, between Fury and Usyk. Money made that possible. But so to the will of the Saudi Arabian investment.

I feel very privileged by how I am treated within the industry. My modus operandi is to try and be consistent. I hope to be asked to contribute into my seventies. I do look at my own life now, as much as I do my profession. I can write forever, and I probably will.

But outside my work in fight sports, I have an interest in playing the piano and acting. I’m working on a book with a brilliant photographer Sonya Jasinski, a coffee table book of stunning photographs and essays on fighters of this era. It is named ‘Call Of The Warrior’ and it is being published at the end of the summer.

I have a couple of acting roles this summer, one in an action movie, and one in a shorter film, now in vogue. In the longer version, I’m playing the part of a tattooed, gold-toothed gypsy and it involves filming for a month in Bulgaria, with an old friend, and former boxer, in Gary Stretch, who has acted with Sir Anthony Hopkins, Angelina Jolie, Colin Farrell, Micky Rourke and others in many films. I believe there are a few big names in the film, including Paul Weller of The Jam, and others, and Gary has encouraged me to take part in this film.

I’m comforted that some of the greatest obras by some of the artists, whom I admire in life, have their greatest success in their 40s, 50s, 60s, or even 70s. And that great artists, amazingly, seem to suffer from imposter syndrome. Everything is a process. There seem to be experts presenting themselves everywhere online these days — on food, exercise, and how we should live our lives. I pruned friends and toxic situations during lockdown. It came from spending time alone. Quite a lot of time. But there is no doubt that a work-life balance is so important. I didn’t always have it in my life. I know to allow myself time for cycling, paddleboarding, good exercise, cooking, and socializing — before work comes and consumes me again like a jealous lover. But the key, I suppose, is no anxiety, and that comes from knowing that what I do is from the heart and that I have a deep passion for storytelling and being involved in a dramatic field where almost anything can happen on any given night. The longer I am involved, the easier it seems to be… but maybe that is just how life is.

Gary Stretch and Gareth A Davies